Apart from Plato’s accounting of Atlantis and Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (see http://www.sacred-texts.com/atl/) there are also other lesser known descriptions of the fabled now-sunken Atlantic Ocean continent. In this short series of blog postings, the focus will be on the subject “when Mu was Atlantis.”

Augustus LePlongeon (1826-1908) wrote on page 66 of Queen Moo and the Egyptian Sphinx(1896,) the following:

“In our journey westward across the Atlantic we shall pass in sight of that spot where once existed the pride and life of the ocean, the Land of Mu, which, at the epoch that we have been considering, had not yet been visited by the wrath of Homen, that lord of volcanic fires to whose fury it afterward fell a victim. The description of that land given to Solon by Sonchis, priest at Sais; its destruction by earthquakes, and submergence, recorded by Plato in his Timaeus, have been told and retold so many times that it is useless to encumber these pages with a repetition of it.”

“Land of Mu” = Atlantis

Le Plongeon placed the original Motherland of Mankind in Central America where Queen Moo ruled (with her brother Prince Coh). After the ‘Mongol Horde’ invaded and conquered them and their advanced civilization, Queen Moo sailed off to the continent of Atlantis. While there she imparted great wisdom, knowledge and technology to the people of Atlantis and in appreciation, they unanimously renamed the continent to “Mu.” After some time, she also migrated to Egypt and imparted their great civilization to them and the legend of Isis. (Obviously, this is a very short version of the entire book, my apologies if I missed anything deemed important.)

In one example discussing the demise of Atlantis, Le Plongeon uses the erroneous translation of the Troano Manuscript by Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg (1814-1874):

“In the year six Kan, on the eleventh Mulac, in the Month Zac, there occurred terrific earthquakes, which continued without intermission until the thirteenth Chuen. The country of the hills of mud, the ‘Land of Mu,’ was sacrificed. Being twice upheaved, it suddenly disappeared during the night, the basin being continually shaken by volcanic forces. Being confined, these caused the land to sink and rise several times and in various places. At last the surface gave way, and the ten countries were torn asunder and scattered in fragments. They sank with their sixty-four million of inhabitants eight thousand and sixty years before the writing of this book.”

Queen Moo and the Egyptian Sphinx; page 147

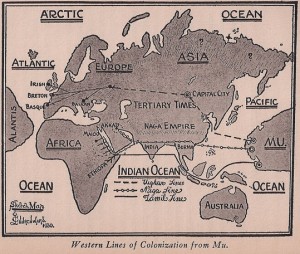

James Churchward wrote the ‘real’ Mu was in the Pacific, using the information he gleamed from the Naacal Tablets he read while in India in the 1870s. From James biography, My Friend Churchey, Churchward and Le Plongeon were acquainted having been among the ‘devotees of the fine arts, poets, musicians, (and) thinkers’ that gathered in the author’s parlor on Sunday afternoons. Percy Tate Griffith also remarks about the Le Plongeons, ‘whom led him (Churchward) to his later devotion to the Continent of Mu, to the series of volumes about its people.’ James also writes he was provided Le Plongeon’s notes to copy. Where Churchward split with Le Plongeon was the location of Mu, although he used many of the same sources (Troano Manuscript, Codex Cortesianus, Akab Zeb inscription, etc.) as references. In the Lost Continent of Mu Motherland of Men (1926), he wrote:

Le Plongeon advanced the theory that Central America was the Lands of the West and therefore the land of Mu, basing his deductions on the contour of the land around the Caribbean Sea, but forgetting entirely that all records establish the fact that the Lands of the West were destroyed and submerged, while Central America to this day is, of course, unsubmerged. This is as plausible as saying that a certain man is dead while he is arguing some point with you.

Both appear to agree that Mu sank, but probably not about the location or identification of the ‘Lands of the West.’

The next installment looks at another description of Mu as Atlantis.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts